Can you save the climate with nuclear power plants that will be flooded by rising sea levels?

Urgenda is a Dutch environmental NGO famous for suing the Dutch Government for not doing enough for climate protection and winning the lawsuit. The Urgenda Climate Case was the first in the world in which citizens established that their government has a legal duty to prevent dangerous climate change.

When we interviewed Dennis van Berkel, legal counsel at Urgenda, we wanted to learn how it is possible for an NGO to run a winning climate case against their government, what background, resources and organisation they relied on for doing that. We also asked about their opinion on nuclear energy, whether they agree with their government that it is one of the solutions to climate change and what huge impacts the changing climate has on the operation of nuclear power plants.

Urgenda supports fossil fuel phase-out and a transition to 100% renewables. What do you think about nuclear power plants in general and about the plans of the Dutch government to build two new units?

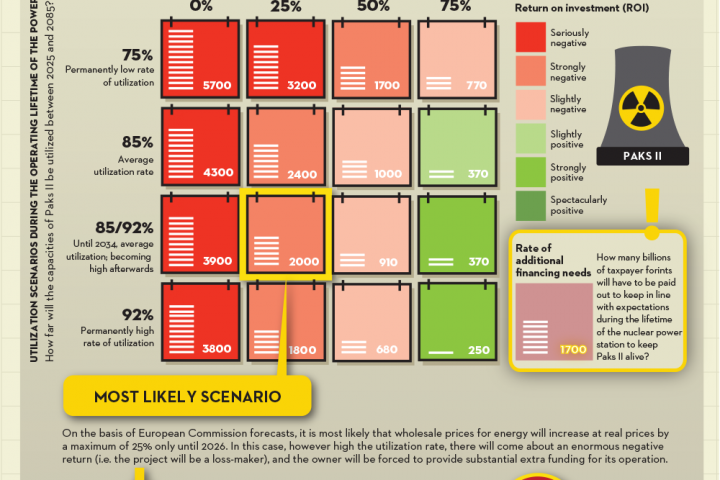

We don’t think it is a good idea to construct new nuclear power plants, especially here in the Netherlands. Renewable energy is becoming cheaper and cheaper by the year, while nuclear products have become much more expensive than initially planned for. So that’s the economics, which doesn’t really play out. Then there is the technical side: renewable energy has to be the backbone of the energy system – and renewable energy and nuclear energy are not a good fit. If you have a very intermittent energy supply from renewables, it becomes very difficult to integrate it with nuclear – it worsens the economic case for nuclear even more.

The third reason is that there is a lot of emission involved in building the enormous structures of nuclear power plants and in all the mining involved. Although there is zero emissions from generation but there are a lot of damaging impacts involved in the entire process. There are also the safety concerns: even if you consider nuclear power not to pose a huge risks in the short term, we still don’t have good solutions for radioactive waste, so the responsibility to deal with that is on future generations.

On top of that we have rising sea levels and rivers that will flood more often or dry up more often. The glaciers are drying up in the Alps and therefore our rivers are becoming rainfed rivers, which are very intermittent, so our rivers drying up in a significant part of the year is a problem already. The River Rhine is a huge river but it is mainly fed in the Alps and if glaciers disappear in the Alps, it will have huge impacts on water flows.

The Delta region of the Netherlands, where there is the currently operating nuclear power plant and where two more units are planned, is particularly vulnerable to climate change. So it is not a wise idea to build a nuclear power plant there if you consider the not negligible risks of very high sea level rise towards the end of the century and 2200, which could render parts of the Netherlands uninhabitable, including the area’s where the new power plants would be build. In case such risks would materialise, how would we move structures such as a nuclear plant when we are dealing with a crisis of having to move parts of the country? That alone is a significant reason for a country such as the Netherlands to not see nuclear energy as an option.

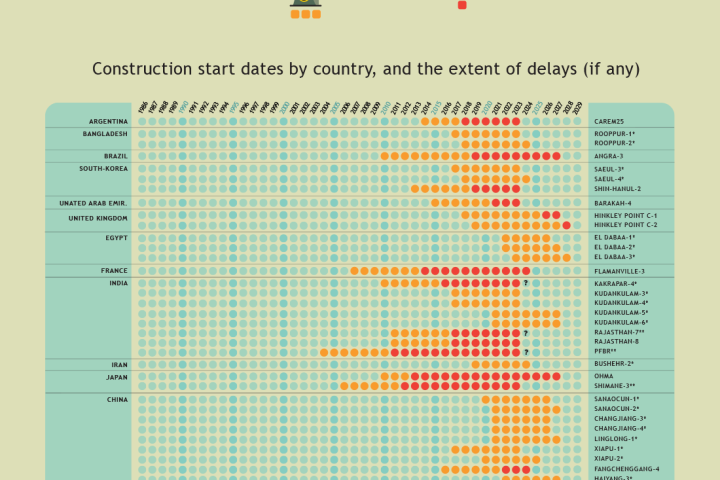

The construction of nuclear power plants is also extremely slow to consider them as a solution to climate change.

Absolutely. And this may very well be one of the main reasons why it is now being proposed. For the first couple of years there are only feasibility studies, so the Government don’t actually need to do anything because there is such a long lead time to actual deployment. Proponents of nuclear power may be using this as a strategy to kick the can down the road so that it becomes the problem of the next government to deal with. Currently a number of feasibility studies are being done, although they actually have all the information they need on the poor economic case and other issues.

What can an NGO do then? Propose suggestions for the government, protest or start another lawsuit?

What we can do is to raise awareness amongst the public about why it is not a solution. I think at the moment our Government haven’t decided on the deployment of the plants yet, whether they are going to be built. There are only feasibility studies and a lot of people think that the outcome of these will show that it is actually not a good idea. A lot of people in the energy sector are very sceptical about it. Most citizens movements are not supportive of nuclear power but ask for more measures in the broader climate protection. I think it would be helpful to have more public debate on nuclear but one of the reasons it is not widely debated yet might be because a lot of people think that this is probably not going to happen.

What were the main reasons for starting the climate lawsuit against the government?

The climate lawsuit was helpful in informing people about the problem and in raising awareness but they were not the main goals. The goal was that we believed the government had an obligation to do something. That this was an obligation based on law. Politics didn’t have the option to say “we are not going to do anything about climate protection”.

We thought politics also has laws and rules and a framework within which it has to operate. Subjecting its people to an escalating climate crisis is certainly not within the sphere that politics can determine because there are fundamental rights that would be violated if they did. Those fundamental rights create obligations on the side of the government to take action - the type of action is up to the government. What we were addressing was the complete lack of action and the fact that the government thought they can’t prevent this problem by themselves and they’ll only act if the whole world acts together, which is currently not the case. We felt politics was not living up to what it had promised to do. In the UN climate treaty of 1992 they had already stated that there is dangerous climate change and emissions have to be reduced to prevent it. Countries agreed at the time that the danger limit was at two degrees and now they have all agreed that danger limit is at one and a half degrees. If politics agrees that this is the danger limit, they have to act upon it. They need to keep to their promises.

What were your hopes at the beginning? And when did you realise that you could win it?

We always felt that we could win it, because we had the law and the arguments on our side but we didn’t know in advance whether the court would be brave enough to take a case which would have a lot of impacts. The moment when I realised we were going to win was in court when the judge was reading out the judgement – the first instance judgement in 2015 at the district court of the Hague. We had an argument that nobody had run before and no court had ever decided upon – so there was no comparison to guess whether we’d win or not. After that judgement in 2015 we felt confident that we could win this at the appeal’s court and the Supreme Court.

What kind of organisation, infrastructure and funding do you need to win such a case?

We do lots of projects with other partners but the core team of Urgenda is 15 – or maximum 20 – people. This was a very intensive litigation, a very big court case, it required a lot of resources. That is one of the main challenges for any NGO – to get funding for it. Urgenda has a number of partners because in addition to awareness raising it also works very hard on the solution side – on how we can reduce emissions. There are also a lot of companies that value our work, and there is big interest in speeding up the transition towards a sustainable, zero-emission economy. We have these partners, we get donations and that is mainly where we get our funding from. Also we had lawyers running the case for reduced fees.

Probably you also did a lot of communication and awareness raising during the case.

Yes, absolutely, and part of this was that the case was run together with 886 co-plaintiffs, so a large group of people were part of the case. That also helped to communicate about the case. And after we won, we became very well-known in national media, so now the media knows how to find us if they want to ask something on climate.

Were you attacked by pro-government media during the litigation?

They were not necessarily pro-government but rather pro status-quo and anti-climate. Indeed there were some media that said that this was completely baseless and it was ludicrous to take climate measures. We are fortunate to have a very strong and independent judiciary, which is by and large very much respected by all media, even by those who are more right-wing and anti-climate. So after the judgement some of the media and opinion-makers disagreed but did it with some respect. After we won in the appeal’s court, people started to think this was not a mistake, not just that an “activist judge” made a wrong judgement. Then mainstream media started to ask the government, “what are you doing to implement the judgement?”. One of the main impacts of the case was that both media and Parliament was calling the Government to respect the judgement by taking more emission reduction measures.

Nice to hear that although some media outlets didn’t agree with you, they didn’t try to discredit you.

There are always exceptions. We also have extreme populist fractions in Parliament that completely deny the existence of climate change. Obviously they had very little good to say about us and they also said that the court was crazy. We also received some political pushback: there were some proposals, especially from right-wing political parties to reduce the opportunities for courts to come to such decisions but these were not successful. And partly because of this pushback, both in the Parliament and media it gained ground that we can’t start destroying our rule of law, we have to protect it, and the court has a legitimate role in such matters.

Recently however, a motion has been passed in Parliament calling on the Minister of Justice to investigate whether it would be necessary to reduce the possibility for NGOs to start this kind of litigation. That was very much in response to our case. The response of the Minister of Justice thus far has been that there are no grounds to change the law on NGO standing before courts as it stands.

To what extent can you tolerate your government’s inaction? When would you start a new lawsuit?

In the past couple of years we didn’t feel the need to start a new lawsuit but that might change and others may feel differently about it. There is a group of people thinking about starting a new lawsuit. We think that the current targets are not sufficient but given the fact that many more measures were taken, we feel that now is not the time for us to start a new case. Moreover, instead of delays, there is rather a push behind more energy efficiency and renewable energy plans because after the Russian invasion into Ukraine there is the realisation that we have to get off gas as soon as possible, in addition to coal. At the beginning of the energy crisis there was the idea that actually we have to go faster. We also see that the take-up of PV panels by home owners and heat pumps for heating – rather than gas heating – has increased in a very short period. It was also because the energy prices went up. And there is no dramatic slowdown yet. We hope that the next government doesn’t slide back. We are going to have new elections and if a much more right-wing government is elected, which is possible at the moment, and it wants to backtrack, it is quite likely that there would be a new lawsuit because the obligations the Supreme Court determined for the Government refer not only to the 2020 target but they also determined that there is a human right obligation – and that obligation is still there.

Can the Urgenda method be adopted in other countries?

At the moment there are more than 80 Urgenda-type cases all over the world according to a report published by the Grantham Institute at the London School of Economics late last year. Seven out of nine cases that were before the Highest Courts of a country had some degree of success. So it is not only a global phenomenon but the cases also have impacts. The IPCC in its latest report described the Urgenda case and described the whole phenomenon of climate litigation and recognised that it can have an impact on mitigation in several countries.

These cases are a very good way of telling the narrative that climate change is potentially catastrophic and will upset our entire society, and we simply have a right not to be subjected to it. We won’t have an organised society and a well-run economy at all if we let the climate crisis escalate. A court can play an extremely valuable role in holding governments to account to actually start doing something about it. Then it is for the Parliament and politics to decide exactly what measures they want to take to tackle the crisis – that is not up to a court. But courts can scrutinise whether they are holding their promises and whether they have any policies in place which are in line with science.

Which date is more important, 2030 or 2050, in terms of reaching climate goals?

If we don’t do anything before 2030, we can’t reach the climate goals. 2030 is absolutely essential, we can’t waste another decade, the previous decade was largely wasted, so we need much more action on emissions reduction. In that sense 2030 is more crucial. 2050 gives some people the sense that they don’t have to do anything yet because it is not there yet. However, after 2030 we have to get to zero as fast as possible.

Do you think the fight against climate change will ever end?

I’m convinced that the era of fossil fuel is ending. We are already in the phase-out. So the fight against fossil fuel at a certain point will stop because there will be no longer any fossil fuel. And if it is not for climate change then it is just purely because of the economics, because renewables are becoming cheaper and cleaner – they are just a better choice.

The only question is how fast that will happen and what will the state of the world be once we have reached that point. It may be very instable because of the pressures of climate change and then the fight will not so much be about pushing out fossil fuel but how to deal with those impacts. There will be large impacts on the stability of states. States are likely to become more vulnerable. If they are hit by one climate extreme and catastrophe after the other, that will obviously also have an impact on how well that state is still able to organise itself. That might lead to political instability. Hopefully we can prevent that by phasing out fossil fuel fast enough.

What do you think about the opinions that we are too late to mitigate and we should focus on adaptation?

It is never too late to do something about mitigation. Every tenth of a degree more does more harm and every tonne of emission contributes to more harm. There is no doubt we will have to continue to push for emission reductions as fast as possible, otherwise there is no prospects of being able to deal with the impacts. At the same time, we can’t prevent the impacts any more because they are already there. So we also have to think about adaptation in Europe – and outside Europe even more and earlier and in more extreme ways. The most severe impacts will be in parts of the world that have contributed the least to this problem. Europe can’t afford to only think about its own mitigation and adaptation and not look at all the impacts of climate change in other parts of the world because Europe can’t survive in a completely instable global society. We have a responsibility and even beyond that responsibility, Europe has a self-interest to also invest in the resilience of people across the globe. So, yes, we have to invest in adaptation but that doesn’t mean we can do anything less about mitigation.